Indians of Iowa

Indians have lived in what is now Iowa for at least 13,000 years. Most archaeological and mapping research has focused on pre-contact Indian sites, the era before Europeans and European goods entered North America. The HILD instead focuses on the last 300 years of Native American history, a period when Europeans and Americans gradually overwhelmed Native economies and took over their lands. Even before Europeans arrived in Iowa, European trade goods such as brass, beads, and hatchets showed up in Oneota sites, the Oneota were the direct ancestors of Siouan tribes such as the Dakota, Ho-Chunk, Ioway, Otoe, Omaha, and Missouria.

The earliest European explorers and traders in Iowa in the 1600s and 1700s encountered natives living in large communities, often fortified villages surrounded by cropland. Fundamental changes occurred in the Native economic systems as traditional trading networks were replaced by commodity trading for hides, furs, and lead, leading to Native dependence on European and American traders. Disease, warfare, and murder significantly diminished Native populations, and entire tribes were forced into new territories, often among traditional enemies. As European trade goods became more common, traditional Native technologies were largely abandoned. By 1800 Indians in Iowa were no longer making pottery and were using European metal pots instead. Stone axes were replaced by steel axes and stone arrowheads were replaced, first by metal arrow points and then by firearms. Native bone and shell beadwork were replaced by glass beads. Traditional woven fabric and hide clothing was replaced by European cloth.

The U.S. government began directly meddling with Indians in Iowa in 1809, when Fort Madison was built. The fort was soon attacked and eventually defeated in 1813 during the War of 1812 by Native forces. After the war, the U.S. renewed its efforts at removing Indians from the eastern U.S., coercing Natives into systematically dividing up their lands and ceding them to the U.S.

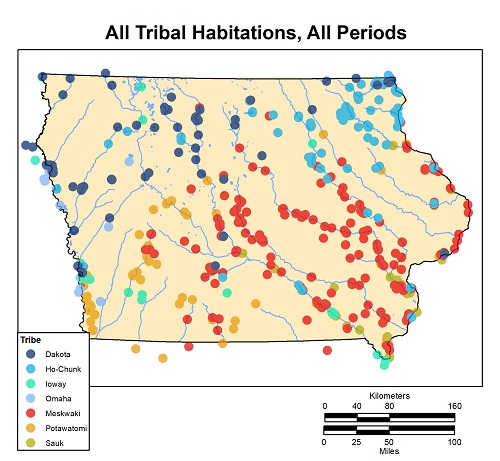

From 1825 until 1840, the main boundary in Iowa was the "Neutral Line," which was intended to separate the Dakota in the north, from the Sauk, the Meskwaki, and the Ioway in the south. Although the Ioway were included in early treaties, they do not appear to have been living in Iowa after the 1830s. Historically, the Ioway had numerous villages in Iowa, many of which were mapped by No Heart in 1837, but these villages have proven impossible to locate with certainty.

In an 1832 treaty, the Neutral Line became the basis of the Neutral Ground, a strip of land on either side of the line, where Ho-Chunk would be forced to relocate from Wisconsin. The Black Hawk Uprising of 1832, a military expedition by Sauk and affiliated tribes living in Iowa into Illinois and Wisconsin led to a massacre of the Sauk and solidified U.S. resolve to remove all tribes from east of the Mississippi. Fort Des Moines No. 1 was built in 1834 in Montrose to control the Sauk. Also in the 1830s, the Potawatomi were removed from Illinois and Wisconsin to what is now the Council Bluffs area of Iowa. In 1840, the U.S. Army built Fort Atkinson and forced Ho-Chunk into the Neutral Ground.

In 1842-1843, Sauk and Meskwaki were forcibly moved to the area that is now Des Moines, where the U.S. Army established Fort Des Moines No. 2. The Meskwaki chose to live farther east, along the Skunk River. In 1845-1846, all Sauk and Meskwaki were supposed to leave the state, but many Meskwaki immediately returned to the Iowa River valley, where they remain to this day, living on a legally recognized settlement established in 1857.

Santee and Yankton Dakota were supposed to have left the state by 1850 but were regularly seen in northern Iowa throughout the 1850s. Fort Dodge was built in 1850 to monitor Dakota near the American frontier. Dakota were essentially removed from the state after the Spirit Lake Massacre of 1857, when settlers in northwest Iowa were attacked by Dakota who had been mistreated.

The presence of Indians in Iowa continued after 1857, not only at the Meskwaki settlement, but also across the countryside. Potawatomi, often led by the enigmatic "Johnny Green," were noted throughout the state, trading peacefully with farmers and visiting towns. Ho-Chunk were also seen journeying throughout Iowa, traveling between their reservation in Nebraska, just across the Missouri River from Iowa, and their Wisconsin homelands. Interactions with settlers and whites were almost always noted as amiable, although racist ideas about Natives led to misguided efforts at forced assimilation of the Meskwaki.

The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and the Native American cultural reawakening of the 1970s led to greater assertion of Native rights. The earliest protests over the mistreatment of Native American burials and human remains began in Iowa, leading to the nation's first state law that protected ancient remains regardless of their ancestry: the Iowa Burials Protection Act of 1976. The law also required the University of Iowa's Office of the State Archaeologist to establish the first statewide Indian Advisory Council for regular consultation with tribes about issues concerning burials and ancient human remains.

The American Indian Movement (AIM) protested mistreatment of Indians in Iowa, and briefly took over a state government building in Des Moines in 1973. Reclamation of land at Blackbird Bend near Onawa by Native protesters eventually led to the reestablishment of control by the Omaha. The Meskwaki settlement now includes more than 7,000 acres. In the 21st century other tribes began purchasing former lands in Iowa. The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska owns land west of Sloan in Woodbury County; and the Ponca and Omaha own parts of Carter Lake.

Native vigilance is still a part of Indian life in Iowa. Mistreatment of burials at Effigy Mounds National Monument led to stronger oversight of the park by tribes in the 2010s. Natives led many of the 2016 Iowa protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline.